What’s great about Xiphosura

In the last few years I’ve moved more and more towards theming my general online presence around horseshoe crabs. There’s a general reason for that, and to properly honour horseshoe crabs for what they are, it deserves to be explained.

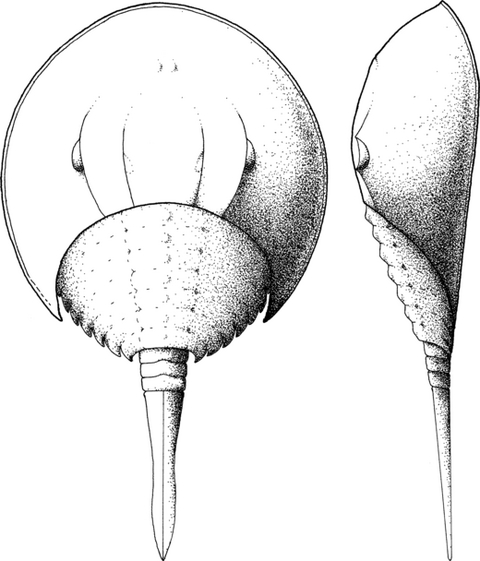

First, we have to start at the beginning. Or, the best we lesser specimens can know of the beginning. Back around the late Ordovician, at least 445 million years ago[1], there was a chelicerate currently called Lunataspis, which looked something like this:

Reconstruction of external exoskeletal morphology of Lunataspis aurora. Figure 5 from [Rudkin2008].

Fast forward 445 million years and another member of the xiphosuran order looks something like this:

Tachypleus gigas. Shubham Chatterjee, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

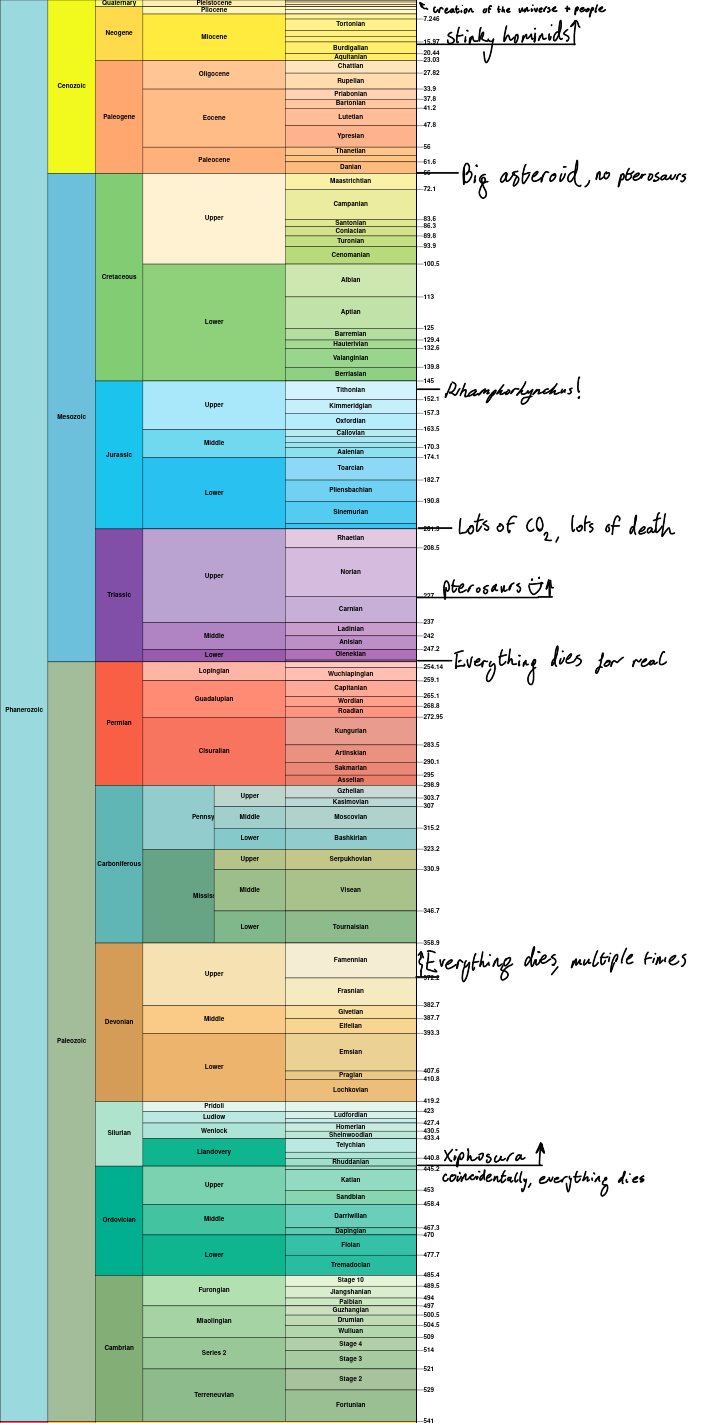

And so— wait, hold up a minute, didn’t we just skip over not mere millenia nor even a myriad of millenia, but a whole 445000 of them? What actually happened in all that time?

Quite a fair bit. (embiggen)

A lot happened. The supercontinent Pangaea did not yet exist, then managed to form in the interim until it broke up again. Entire taxa came and went, and the taxa they were part of also came and went as all five ‘famous’ extinction events took their toll, with surviving taxa each time diversifying only to be wiped out in the next one. And during all of this, horseshoe crabs as a group endured.

Well so what, lots of things endured. Plants are still around. Arthropods, molluscs and vertebrates all managed. But for all these groups, how many modern members so strongly resemble their Ordovician counterparts? Fish, perhaps. Sponges. Bacteria are still little microscopic prokaryotes.

But horseshoe crabs are not a huge or diverse group. In fact, there is a grand total of four extant species. They haven’t in any particular sense ‘dominated’ their environment or caused an ecosystem to adapt around them. Now a quick internet search will easily turn up dozens or hundreds of ‘living fossils’ and it’s by no means a contest or some bizarre pissing match. But out of all the examples, I do think horseshoe crabs are quite unique in terms of how little they resemble any other taxon.

Did you know horseshoe crabs swim— well, like this? © Jürgen Freund, www.jurgenfreund.com

Horseshoe crabs are so fundamentally different from anything else, and yet – they’re not flashy, extravagant, widespread or apex predators or even really all that noteworthy in any particular way. But they routinely continue to exist, not so much despite the world but almost in spite of it all. They’ve found a place in an uncaring and indifferent reality, and they’re not budging no matter what anyone thinks.

And I think it’s rather admirable.

RUDKIN, D.M., YOUNG, G.A. and NOWLAN, G.S. (2008), THE OLDEST HORSESHOE CRAB: A NEW XIPHOSURID FROM LATE ORDOVICIAN KONSERVAT-LAGERSTÄTTEN DEPOSITS, MANITOBA, CANADA. Palaeontology, 51: 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4983.2007.00746.x